TLDR - There are many interrelated components that contribute to digestion. It is important to investigate all pieces when troubleshooting digestive issues.

Chewing:

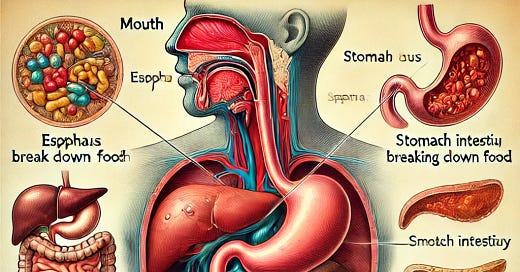

Importance of Chewing: Digestion begins in the mouth, where food is chewed (masticated) into smaller pieces. This breakdown is important as it increases the surface area of food, making it easier for enzymes to act upon it later in the digestive process. Chewing also mixes food with saliva, which contains the enzyme amylase that begins the breakdown of carbohydrates.

Saliva: Saliva not only contains digestive enzymes but also lubricates the food, forming a bolus that can be easily swallowed. Adequate chewing ensures that food is well mixed with saliva, promoting easier swallowing and more efficient digestion in the stomach and intestines.

Swallowing

Once chewed, the food is pushed to the back of the throat and swallowed, entering the esophagus. The esophagus uses muscle contractions to move the food down into the stomach.

Stomach

Stomach Acid: In the stomach, food is mixed with gastric juices, which include hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes like pepsin. The acidity of the stomach (pH 1.5-3.5) is important for breaking down proteins into smaller peptides. Adequate stomach acid is needed to activate pepsin and sterilize the food by killing potential pathogens.

Chyme: The stomach churns the food into a substance called chyme. This process is needed for the digestion of proteins and the absorption of certain nutrients.

Liver

The liver produces bile, a substance needed for the digestion and absorption of fats. Bile contains bile salts, which emulsify fats, breaking them down into tiny droplets that enzymes can more easily act upon.

Gallbladder

The gallbladder stores bile and releases it into the small intestine when needed, specifically after the ingestion of fatty foods. Efficient bile production and release are essential for the proper digestion of dietary fats and the absorption of fat soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K).

Small Intestine

Entry into the Duodenum: Chyme is gradually released into the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine, where it mixes with bile and pancreatic juices. Bile, produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, emulsifies fats, breaking them down into smaller droplets that enzymes can more easily digest.

Pancreatic Enzymes: The pancreas secretes a variety of enzymes into the small intestine, including lipase (to digest fats), amylase (to digest carbohydrates), and proteases (to digest proteins). These enzymes are required to break down macronutrients into their absorbable components (fatty acids, sugars, and amino acids).

Microbiome: A healthy gut microbiome helps break down complex carbohydrates and fibers, producing short chain fatty acids that nourish the intestinal cells and contribute to health. The microbiome produces enzymes that assist in the digestion of food components that human enzymes cannot digest.

Nutrient Absorption

Intestinal Lining: The small intestine's lining is covered with tiny finger like projections called villi and microvilli, which increase the surface area for nutrient absorption. A healthy intestinal lining is important for absorbing nutrients while preventing harmful substances from entering the bloodstream. It acts as a selective barrier, allowing only beneficial substances to pass through.

Tight Junctions: The cells of the intestinal lining are held together by structures called tight junctions, which regulate the passage of substances. If these junctions are compromised (a condition often referred to as "leaky gut"), harmful substances like toxins and undigested food particles can pass into the bloodstream, potentially leading to inflammation and other health issues.

Large Intestine

Transition to the Colon: Once most nutrients are absorbed, the remaining waste, now mostly indigestible fiber, water, and dead cells, moves into the large intestine (colon). The colon's primary function is to absorb water and electrolytes from this material, transforming it into solid stool.

Microbial Fermentation: The large intestine is home to a large population of bacteria that further ferment some of the indigestible fibers, producing gases and additional short chain fatty acids that contribute to colon health.

Stool Formation and Excretion: The waste material is compacted into feces, which are stored in the rectum until they are expelled from the body.